ZEE ZEE IN CONCERT

Esplanade Concert Hall

Sunday & Monday (23 & 24 January 2022)

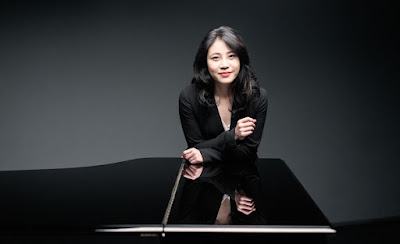

Around the Chinese New Year season every year, Esplanade presents an ethnic Chinese pianist in recital as part of its Huayi Chinese Festival of Arts. This year’s two recitals by Zee Zee were however not in this festival, but the Classics Series and co-sponsered by Kris Foundation. This is Kris Foundation’s biggest coup to date as Zee Zee is none other than Zhang Zuo (or Zuo Zhang), joint First Prize winner of the First China Shenzhen International Piano Competition, and finalist at the Queen Elisabeth and Van Cliburn International Piano Competitions.

Her career follows the familiar trajectory of young Chinese pianists, students of Shenzhen-based pedagogue Dan Zhaoyi such as Li Yundi, Chen Sa and Zhang Haochen, who pursued further studies in the West (Eastman and Juilliard in her case) before hitting the international big time. The choice of repertoire in both recitals also demonstrated a sophistication that went beyond the familiar Beethoven-Chopin-Rachmaninov axis beloved of most Chinese pianists.

Opening the first recital with Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit must be a terrifying prospect, but little fazed ZZ, who was attired in a tinsel-laden black top, matching pants and 6-inch stilettos. The right hand complex tremolos were as even as one could hope for in the opening Ondine, the water sprite whose lovelorn escapade on land wreaked a terrible vengeance. A most evocative portrayal of the fluid realm, its glistening glissandi and sweeping arpeggios handled with delicacy and vehemence to equal measure made it a thrilling ride.

In the central movement Le Gibet, the ceaselessly tolling bell in B flat cast a hypnotic spell, over which shadowy figures gathered to witness a hanging. The morbid speculation then segued seamlessly into the malevolence of Scarbo, whose knock-kneed scampering is the very stuff of Gothic nightmares. ZZ’s take no prisoners approach served this music to the tee right down to the evil goblin’s final cackle. How did she accomplish such acrobatics with stilettos? Simple, she had taken her left shoe off!

The harmonic ambivalence of tonal Gaspard could only lead to Arnold Schoenberg’s Three Piano Pieces Op.11 (1909), the first ever atonal piano pieces ever written. If any thematic links were to be found joining Ravel and Schoenberg, that might be the three-note motifs in the first and second pieces which may be considered extensions of the three-note motif that opens Scarbo. ZZ gave a very absorbing account of these rarefied pieces (heard perhaps for the first time in Singapore?), balancing transient lyricism with knuckle-dusters to the ears. She brought a score on stage, but hardly had to look at it. Referring to my score on hand, she hardly had a wrong note.

The inspiration for the Ravel was certainly Franz Liszt, whose three pieces from three books of Années de pélérinage (Years of Pilgrimage) completed the first recital. ZZ took an epic view to the popular Vallee d’Obermann, a tone poem in miniature, reveling in its harmonic vagaries and then letting rip in the tempest scene. Travelling from Switzerland to Italy, Le jeux d’eau a la Villa d’Este and its water spouts left little doubt that this essay was the fount from which Ravel’s Jeux d’eau and Ondine sprang forth. The programme was making even more sense now.

Spiritual inspiration gave way to the earthly domain of Neapolitan folksong in the rip-roaring Tarantella from the Venezia e Napoli book. The spellbinding speed which she took at the outset of the vertiginous dance seemed scarcely credible, and there were smudged notes aplenty. And how could she possibly build from there? The central folksong section provided some respite as well as several hair-raising cadenzas which almost seemed like childplay. When it came to the final romp, it was imperious and full-blooded. Nothing subtle about this piece, but ZZ had the blood and guts to make it work. The applause was tumultuous, and her encore of the Intermezzo from Schumann’s Faschingsschwank aus Wien was a rehearsal for her second recital.

A different pianist, however, turned up to perform the second recital. Now attired more conservatively (had she run out of snazzy outfits?), Zee Zee appeared like she had aged overnight. For some reason, she played only one of three Clara Schumann Romances (Op.11), a beautiful song without words from which she brought the best with sensitive passage work and judicious pedalling. That was the highlight of the evening, which went south from there.

Robert Schumann’s Faschingsschwank aus Wien (Carnival Jest in Vienna, Op.26) received a strong reading as far as the notes went, but the whimsical aspects of the music (akin in spirit to his Papillons Op.2 and Carnaval Op.9) were not fully realised. More could have been made of the sly quotes from La Marseillaise and Beethoven (Sonata Op.31 No.3) inserted into the opening movement, but the tender Romanze that followed came through most prettily. The last three movements picked up on speed progressively, with the Finale breaking all speed records, almost careening off the tracks before coming to a sturdy close. Lots of haste, but not so much jest.

The biggest disappointment was Brahms Handel Variations, which simply put, were mishandled. The statement of the theme was the best part. Each of the variations that followed were fraught with danger and mishaps, as she ploughed into deeper trouble as the work progressed. As soon as she hit a snag, she would conclude the variation and swiftly move on to the next one with further inherent risks. From hot soup, onto the frying pan, and into the fire. She did however observe the cardinal rule of all concert pianists: never stop playing. One really felt for her in this ordeal which closed with a mighty fugue, summoning every ounce of reserve that was left in a fast depleting tank.

There was loud and grateful applause for her toils, but no encore, which was just as well. Count this as a bad day at the office, as the hero of the night before had become a spent force this evening.