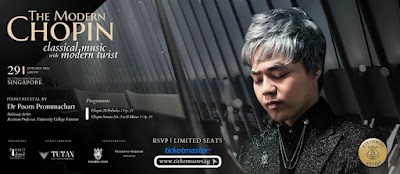

THE MODERN CHOPIN

POOM PROMMACHART, Piano

Victoria Concert Hall

Sunday (29 January 2023)

What is the “Modern Chopin”? Was not the Poland-born and Paris-domiciled pianist-composer an early Romantic? And did the darling of the salon concert not die in 1849? Stereotypes of Chopin as a sickly, tuberculous and effete artist suffering for the love of his art and succumbing to a premature demise still abound. So how do our modern ears relate to the piano music of Frederic Chopin?

|

| How should we view Chopin? Delacroix's painting, a late 1840s daguerreotype or Hadi Karimi's modern 3D rendering? |

Young Thai pianist Poom Prommachart, once a student of Dang Thai Son (first ever Asian winner of the Chopin International Piano Competition, in 1980), provided many of the clues. One might mistake this artist as fashionista, ambassador for the Canadian luxury brand Kaimirra Tutan, to be more style than substance, but the proof of a pudding was in its eating.

One feared the worst when a signpost at the door listed Chopin’s 24 Preludes (Op.28) as lasting for 48 minutes. The rolled chords of the opening Prelude in C major (marked Agitato) were taken very leisurely, but that allowed each note to resonate longer, and when the next number in A minor (Lento) plodded by like a funereal dirge, one became almost certain of Poom’s intentions. When most are willing to spin out all 24 pieces as one indivisible whole, Poom instead regarded each piece as its own discrete and sparkling gem. With the audience heeded not to applaud between numbers, the succession of Preludes became all the more coherent.

Never has a work by Chopin displayed more heterogeneity in mood, harmonies, texture and tempi, yet held so well with some kind of spiritual “spatial and temporal glue”. It is the performer who holds the secret to that glue which eluded even the composer himself. Chopin only performed selections or small groups of Preludes, and never all 24 at one sitting. It was Poom’s singular vision that made this long sequence work. He had no need to gild the lilies in “simple” ones, as the numbers in E minor (No.4), B minor (No.6) and A major (No.7). And when virtuosity was called for, in F sharp minor (No.8), B flat minor (No.16) and the final D minor (No.24) for example, he unleashed all the weapons of his formidable arsenal.

More telling was the sheer beauty and poetry he brought out in F sharp major (No.13) and A flat major (No.17). And what of the famous D flat major (No.15), popularly known as the “Raindrop”, reliving the bad weather of Mallorca where Chopin and George Sand had made their retreat? With Poom, one was reminded not of acid rain but the pain of constant stabs to the heart, as a relationship breaks down irreversibly and irremediably. Raindrops were but a front for something deeper and darker.

The performance did not take 48 minutes, but rather closer to 36 minutes, which is about right. No performance of the Chopin Preludes has captivated this listener as much as this since the late-lamented Fou Tsong’s in the same hall in 1993, some thirty years ago.

The recital’s second half belonged to Chopin’s Sonata No.3 in B minor (Op.58), a performance no less trenchant or absorbing. The first movement delighted in the dissonances of Chopin’s late period and through all this, the lyrical second subject was perfectly brought out. There can be no melody as exquisitely beautiful as this one. The exposition repeat was omitted, perhaps rightly so as to keep tautness to the proceedings. The etude-like Scherzo was whipped off effortlessly and it was ironically in the nocturne-like Largo where some concentration was lost. Nevertheless, the romping Rondo finale, with the ante upped each round, more brought the sonata to a thrilling end.

As encores, Poom offered an improvisation on a Chinese song (Unending Love) to greet the Lunar New Year, and the most edge-of-the-seat version of Liszt’s La Campanella thought possible. And he had the cheek of declaring he had not enough practice. Most importantly, The Real Chopin made the audience listen to Chopin with new pairs of ears.