FIRST STEP

Singapore National Youth Chinese Orchestra

Singapore Conference Hall

Saturday (18 December 2021)

It has long been a misconception of mine that Chinese classical music, specifically music played on traditional Chinese instruments, is a preserve of the senior demographic. I have often remarked that audiences at Singapore Chinese Orchestra concerts were mostly boomers and older, and more young people needed to come to these concerts lest this hallowed tradition becomes extinct. This evening I heaved a sigh of relief, to find that the Singapore National Youth Chinese Orchestra (SNYCO) is the very antidote to this notion of musical extinction. Encouragingly, more young Singaporeans are learning to play Chinese instruments, and consequently more young composers are writing works for these instruments.

Conducted by Quek Ling Kiong, the SNYCO gave its first concert in almost two years, the hiatus caused by the Covid pandemic’s disruptions. It opened with two movements from Lo Leung Fai’s Echoes of Spring, almost a Chinese version of Rossini’s Sonatas for strings or Mendelssohn’s Symphonies for strings. The bowed strings – huqins with four cellos and two double basses – were in fine form despite not having played for a long while. The prestidigitation achieved in both fast movements was impressive, the opening serving as a warm-up for the furious finale.

A larger mixed ensemble converged for young Singaporean composer Jon Lin Chua’s Princess Miao Shan, a symphonic poem receiving its Singapore premiere. Inspired by the legend of how Guanyin Boddhisatva (the Goddess of Mercy) came to be, it is a colourful melange of sound beginning tumultuously and a suona solo. Despite its modern idiom, there was still room for a big melody evoking the open country and broad landscapes. Percussion provided the dramatics and a poignant dizi solo paved the way for music which portrayed profound sadness and tragedy, representing the ultimate sacrifice the eponymous princess was to make. Ending quietly rather than in the customary blaze of glory gave the work an extra dimension of sobriety it needed.

There were two concertante works, the first being Lo Leung Fai’s Joyful (Xi) with Leong Kim Yang’s dextrous dizi solo. Scherzo-like for most part, this dizi occupied the piccolo register, its timbre and nimbleness suggesting that mischief and pranks were also part of its definition of joy. The virtuoso role included two really demanding cadenzas which Leong nailed most impressively despite his relative youth, having joined the orchestra just two years ago.

Sulwyn Lok’s Sand Mystique was the second concertante work, essentially a concerto grosso for erhu/zhonghu, pipa and darbuka (a Middle-Eastern hand-held drum). Soloists Li Siyu, Chen Xinyu and Tan Sheng Rong stole the show in a work which opened Mahler-like (the pedal-point of his First Symphony) in its rapt evocation of dawn in the desert. The idiom was distinctly Middle-Eastern or Central Asian whichever direction one travelled, with the aromatic flavours of the exotic Silk Road richly relived. The accompanying orchestra also contributed with a spot of rhythmic clapping in this lively dance built upon vigorous ostinatos.

When writing music about outer space and the cosmos, the obvious influences are Holst or Hollywood. Chen Si Ang’s Interstellar went for the latter in a sonorous soundscape accompanied by lighting illuminations that evoked the Milky Way and distant galaxies. The opening was quiet, with dizi solo breaking the silence, then came ostinatos of The X Files variety, leading one on a journey of wonderment. The quote from Oscar Wilde, “We are all in the gutters, but some of us are looking at stars” was ever-present as the odyssey closed with typical bombast that such a title foretold.

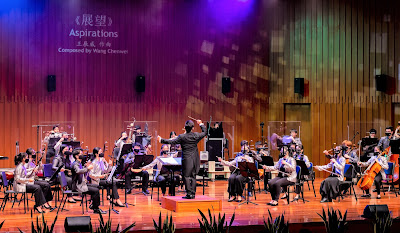

Closing the 75-minute long concert was present Singapore Chinese Orchestra composer-in-residence Wang Chen Wei’s Aspirations, composed as far back as 2008. This is an extended version of its original, which revelled in the cheerful melodies heard in television and film music depicting heartland life. Nothing wrong with that, but as soon as new ideas are wanting, always rely on the trusty fugato. That spot of Bachian counterpoint – with sheng, dizi and zhongruan thrown into the mix - was a welcome departure as the concert wound to a happy and optimistic conclusion.

The Singapore National Youth Chinese Orchestra and its talented young musicians represent the bright future for Chinese instrumental music in Singapore. This bright future is in the best of hands, and long may the enterprise thrive.

All photographs by the kind courtesy of SNYCO/SCO.

No comments:

Post a Comment