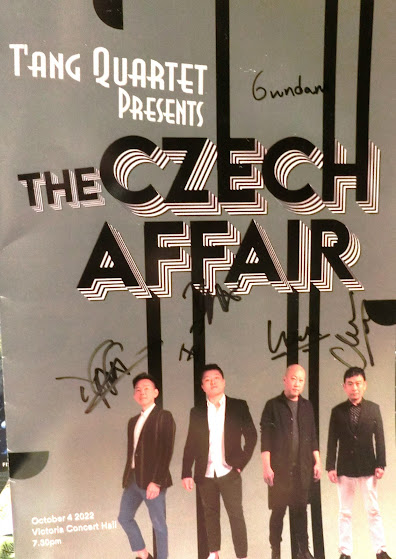

THE CZECH AFFAIR

T’ang Quartet

Victoria Concert Hall

Tuesday (4 October 2022)

For the final concert of its 30th anniversary season, T’ang Quartet went back to its Bohemian roots. Formed in 1992, the quartet was mentored by Jiri Heger, the Czech (and original Bohemian) who was Principal Violist of the Singapore Symphony Orchestra. The first two commercial recordings which T’ang Quartet produced were of Czech music, creating a stir of interest when first released. This concert was a return to those early hits from almost twenty years ago.

|

| Ng Yu Ying and Ang Chek Meng with their mentor Bohemian violist Jiri Heger |

The quartet opened with Josef Suk’s Meditation on the Old Czech Chorale Saint Wenceslas, which has nothing to do with the Christmas hymn Old King Wenceslas. It is instead a sober work, with Han Oh’s viola having the first voice. With the others joining in, the theme and its development began to emerge. Most apparent is the close cohesion and consistently robust sonority the foursome achieved in this slow moving work which gradually built to a climax. One might consider this a Czech counterpart to Barber’s Adagio for Strings, for engendering the same kind of deep-seated feelings and emotions.

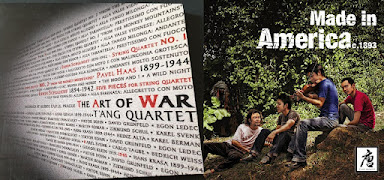

Next came the opening strains of Antonin Dvorak’s String Quartet No.12 in F major (Op.96), better known as the American Quartet because the composer had written it during his sojourn in the US of A. This was the selling point of the quartet’s second CD recording, Made in America. Folk rhythms from its outset, thought to be influenced by African-American music, came vigorously to the fore. This was vibrant music which got the treatment it deserved, and the quartet later switched modes for the slow movement’s lament. Whether its inspiration was an Eastern European dumka or African-American spiritual is a moot point, as both possess the quality of a long breathed sigh, well-captured in this heart-felt reading.

|

| Photo: Cara van Miriah |

The quaint pentatonic melodies of the third movement’s dance were lively to say the least, and so was its execution with pin-point accuracy and attention to its drumming rhythms. Again it was difficult to differentiate Dvorak’s treatment of vernacular material (whether Bohemia or Spillville, Iowa, where he spent a summer in 1893), except to say it was quintessential Dvorak. The energetic and rhythmic finale, where the quartet went full-voiced and full throttle, which made for an exciting conclusion.

|

| Photo: Cara van Miriah |

Its ghostly opening with seemingly random string figurations soon coalesced into a pastoral scene in the movement titled Landscape, depicting the open countryside of the Monkey Mountains. There is nothing racist about the nickname for the Czecho-Moravian highlands which Haas and his friends often retreated to. The influence of Haas’ teacher Janacek is unmistakable, with the repetitive use of simple rhythmic motifs, often derived from folk music. The next movement Coach, Coachman and Horse served as a scherzo, one filled with outrageous portamenti (string slides), creaking and groaning, stops and starts, suggesting the cart was drawn not by some thoroughbred, but a reluctant mule, affording a bumpy ride for all concerned.

The Moon and I, the obligatory slow movement, saw very fine muted unison playing, in a version of “night music” rather different from Bartok’s. It nevertheless still got under one’s skin by its evocation of mystery and sheer intensity. The final movement Wild Night was literally what is described, an intoxicating dance filled with jazz and dancehall vibes which were the craze of 1920s Europe. This got even more interesting with the inclusion of drums, handled confidently by young Thai percussionist K.Gun Mongkolprapa, a student of Yong Siew Toh Conservatory. There were even moments for reflection before all hell broke loose for a riotous heavy metal finish, cueing a chorus of cheers.

|

| Photo: Cara van Miriah |

No comments:

Post a Comment